Food waste is an ethical and an environmental problem. It’s also a business opportunity, ready for innovative solutions.

“The Basics” provides essential knowledge about core business sustainability topics.

Food waste is an ethical problem. Globally, 1.3 billion tons of food go to waste, while 1 in 11 people (nearly 690 million [1]) face hunger. Food waste is also an economic and environmental problem. Resources that go into producing uneaten food, like labor, natural resources, and fertilizer, are wasted.

So the bad news is there’s a long way to go when it comes to reducing food waste. But there’s also opportunity and potential for innovation. The food waste market is valued at nearly $47 billion, according to a 2019 report from Future Market Insights.

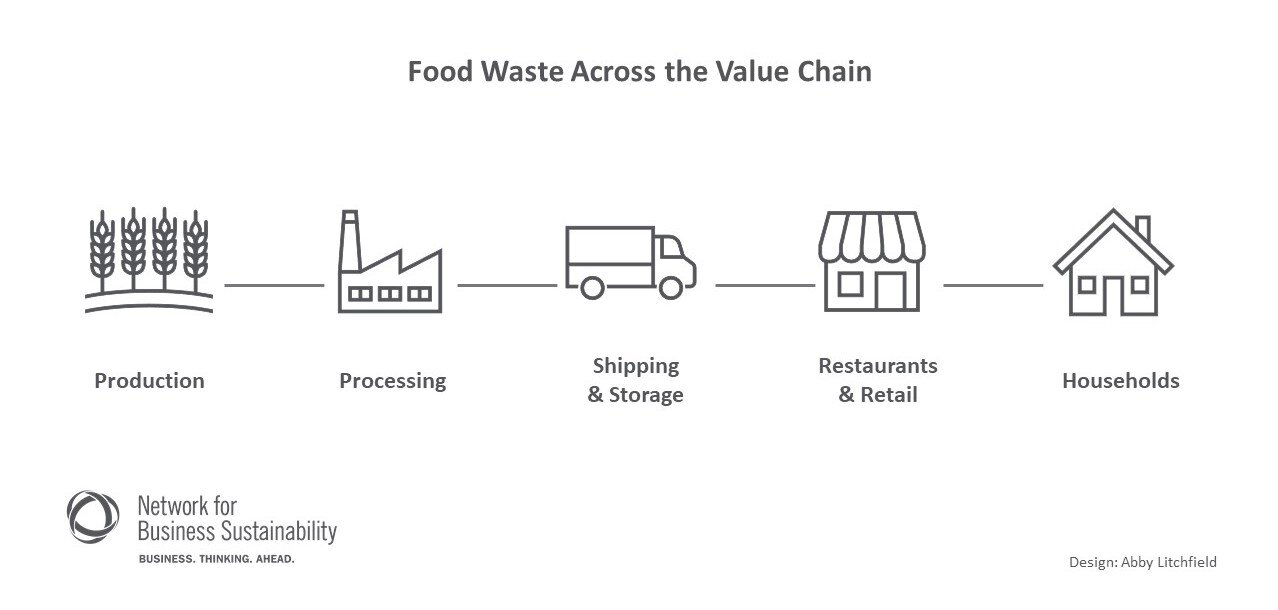

Companies across sectors are involved in finding solutions to food waste, according to Alexandria Coari, vice president of capital, innovation, and engagement at food waste nonprofit ReFED. That’s because food is wasted at every stage of the supply chain, from when it’s first produced on farms to when it’s consumed (or rather, not consumed), and every step in between.

Many companies are already taking action, whether they’re small start-ups with an innovative product or established institutions. But there’s plenty of room for others to get involved.

This article covers:

the challenge of food waste

the range of solutions

the businesses and initiatives making a difference

tips for implementing change in your organization

Food waste is a challenge – and opportunity

Every year, about one-third of all food in the world is lost or wasted across all stages in the food supply chain. This translates to $940 billion of economic losses annually. While consumers tend to be more responsible for food waste in high-income countries, food suppliers (from producers to processors and distributors) generate large amounts of food loss and waste in all countries.

In the U.S., for example, 35% of edible food goes uneaten. “Financially, what that equates to is over $400 billion a year that is grown, transported, processed, and ultimately thrown away,” says Coari of ReFED. “That ends up being about 2% of [U.S.] GDP. That’s a huge amount of waste in terms of financial resources.”

Food waste is costly in environmental terms as well. Agriculture uses up over a third of global land area and over 70% of freshwater withdrawals. Food waste is responsible for 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions. “If it were a country, food loss and waste would be the third-largest emitter after China and the United States,” report cross-sector coalition Champions 12.3.

Waste means opportunity

Efforts to reduce food waste are already benefitting companies and society. The Champions 12.3 report analyzed 700 food and hospitality companies in 17 countries that took actions to reduce food waste. The median return on investment was 14:1, with benefits especially high for companies that had had limited waste reduction efforts when the study was conducted. Looking to the future, a 2020 ReFED analysis found that investments to halve food waste by 2030 would result in a 5:1 return, in addition to creating thousands of jobs, reducing water use and greenhouse gas emissions, and saving billions of meals.

Innovative food waste solutions

There are many potential solutions that can be implemented by stakeholders throughout the value chain, whether it’s taking advantage of existing strategies or making use of new, emerging tools.

Here’s are some exciting approaches:

Shelf life extension technologies reduce food waste at the consumption stage by allowing perishable foods to last longer. Apeel produces sprays made from plant matter that slow the spoiling process; a pilot test of Apeel-treated avocados found a 50% reduction in wasted avocadoes. The company received a $1 billion valuation last year. Other companies extending shelf lives include Mori, which creates a protective coating based on silk proteins, and Hazel, which produces sachets that are placed in boxes of produce. Both companies successfully raised rounds of funding last month.

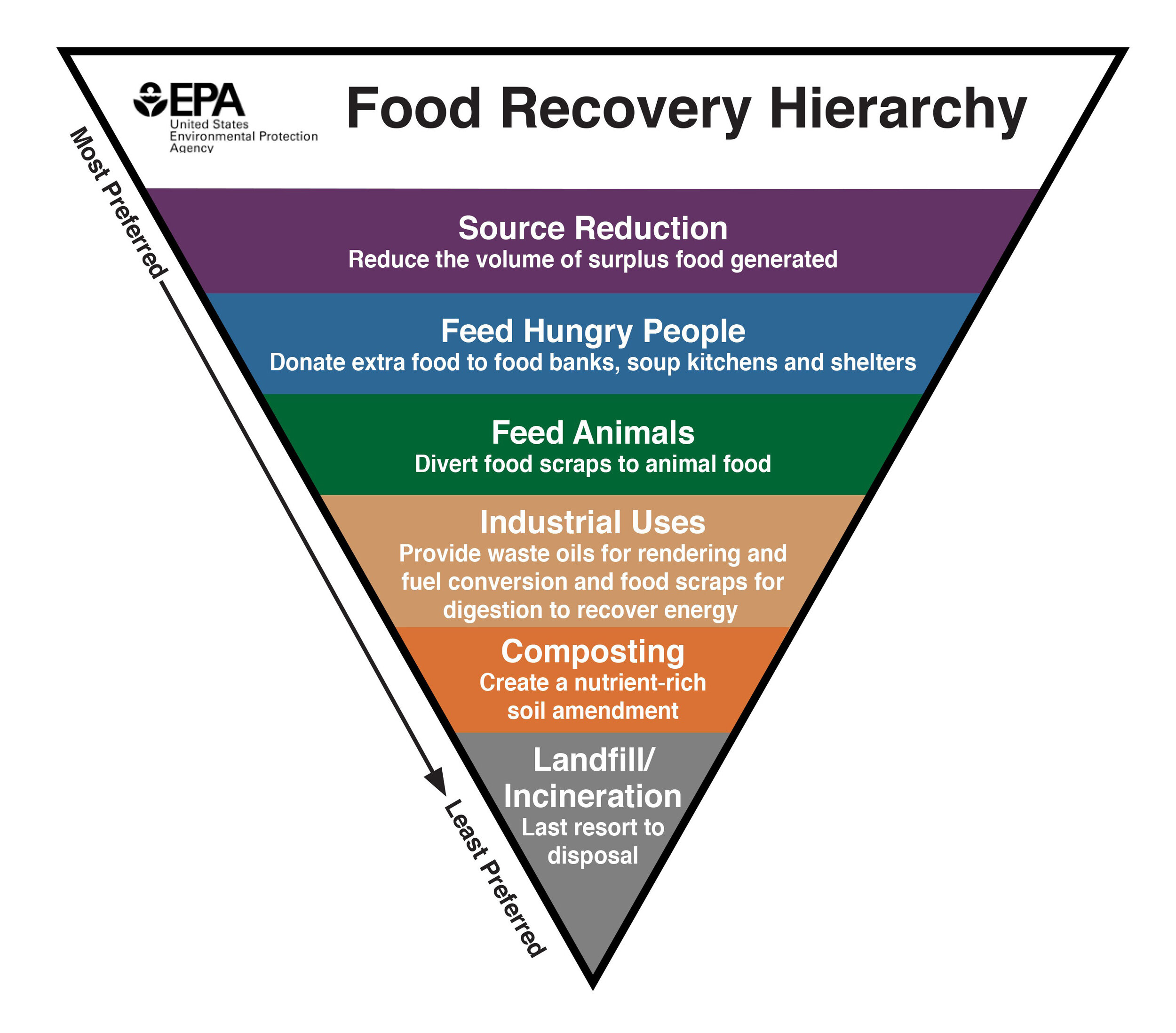

Upcycling finds uses for unused food rather than composting it (or worse, incinerating or landfilling it). With upcycling, surplus food or food production byproducts can become valuable ingredients for another product. Examples of upcycled foods include banana chips made from off-grade bananas, or pickles using cucumbers that would otherwise have gone to waste. Upcycling is gaining traction: 39% of consumers want to buy upcycled foods, according to a 2019 survey, and the Upcycled Food Association has developed a certification standard for ingredients and products.

It can be tough to reliably source inputs for upcycling, but organizations exist to broker connections between companies with compatible interests (examples include CTTEI in Montreal and NISP in Vancouver). Collaborations can happen between two businesses or an entire ecosystem of businesses. Canada’s first “circular food economy,” in Guelph-Wellington, has made partnerships a priority, with a goal of creating 50 circular businesses and collaborations by 2025.

Enhanced demand planning is a new way to look at managing demand and has the potential to create over $5 billion in value, ReFED estimates. Food retailers use data-driven insights to order with greater efficiency, limiting overbuying and food waste. Companies working in this space include Afresh and Shelf Engine, which both use AI to inform ordering processes.

Food waste solutions in companies

It’s easy to focus on the cutting-edge technologies. But any company can do better in reducing food waste. A great tool is the ReFED Insights Engine. Use it to do a cost-benefit analysis of different food waste reduction solutions. The analyses address different industries and are based on impact goals; the Engine also identifies U.S.-based solutions providers. In Canada, non-profit Provision Coalition and Enviro-Stewards offer food waste reduction services.

Inside and outside the food sector, companies are committing to change. For example, 200 food suppliers around the world have promised to halve food waste in their operations by 2030 through the 10x20x30 initiative. Ten large food retailers and food service providers, including Walmart, Kroger, and IKEA, each engaged 20 of their suppliers to reduce food waste across the supply chain.

“A lot of businesses, regardless of whether you’re in food or agriculture … are making sustainability commitments,” says ReFED’s Coari. “Food waste is a huge, low-hanging fruit within those businesses even if it’s not their day-to-day operations. If you’re any kind of business that has made sustainability or any kind of climate commitment, food waste is the number-one solution that’s gonna get us there.”

Google is an example of a large organization that’s not a food business at its core but has leveraged its role as a food service provider to employees. Using data to track and prevent food waste (“enhanced demand planning”), Google avoided 9.2 million pounds of food waste across 189 company cafes between 2014 and 2020.

Businesses can play an additional role: educating consumers. In developed countries, consumers and retailers generate the greatest share of food waste. And in the U.S., most food waste happens at the household level. Businesses can educate their consumers on food waste and support positive behavior changes to drive collective action.

For anyone working on food waste, it’s important to keep in mind the highest value actions, as identified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Better matching food produced to needs is top priority.

3 tips for achieving change

Like any change, implementing solutions to food waste can be challenging. Here are some steps that can help ensure food waste gets reduced.

1. Have someone own the profit and loss (P&L) for food waste. Often, organizational silos and misaligned cost and benefit structures mean no one takes ownership over food waste. Financial benefits come in different areas: from buying the right amount of food, selling purchased food, and donating food rather than sending it for costly disposal. Integrating responsibility can be challenging.

“It’s just trying to work through bureaucratic and cultural norms within institutions where ultimately that ownership doesn’t belong to one department or one person,” Coari says.

2. Change mindset. Food waste reduction requires employees to think differently about their responsibilities, report leaders at Canadian non-profit Provision Coalition. Engineering solutions alone aren’t enough, they note: “Any shift in behaviour is fundamentally a human adventure, not a technical one.” This five-step model can help achieve mindset change.

3. Network and partner. As with so many sustainability issues, it’s hard to address food waste on your own. Organizational boundaries are likely to blur as firms collaborate to integrate their operations to upcycle each other’s waste streams, says Jury Gualandris, a supply chain management expert at Ivey Business School. That engagement can require new activities and lines of responsibility. Who organizes collection and redistribution services? Who pays and who benefits? New partnerships, especially with non-traditional partners, need to emphasize value co-creation.

Future food waste solutions

While innovators have explored food waste solutions at many levels, there’s more to be done and still more chances for interested companies to address gaps in the market. Just look at farming: In North America, 21% of waste happens on farms, providing ripe conditions for a motivated disruptor to step in.

If there’s one positive lesson we can take from the work already done on food waste, it’s that addressing the issue doesn’t exclusively have to rely on bigheartedness or philanthropy. Everyone involved stands to benefit, from company to consumer to planet.

[1] With the covid-19 pandemic, an additional 83-132 million people will likely become undernourished.

Review of this article was provided by Dr. Jury Gualandris, assistant professor, Operations Management & Sustainability, at the Ivey Business School. Jury studies the institutional, operational and economic challenges associated with the development and functioning of circular supply chains. He’s part of an innovative partnership between the Ivey Business School and Guelph-Wellington’s circular food economy, studying how firms can establish and sustain effective circular supply chains.

About the Series

“The Basics” provides essential knowledge about core business sustainability topics. All articles are written or reviewed by an expert in the field. The Network for Business Sustainability builds these articles for business leaders thinking ahead.

Add a Comment

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.